Please note that we will be reprinting this anthology with Thomas King’s story “Where the Borg Are” removed from the Indigenous Futurisms section and Eden Robinson’s story “Terminal Avenue” added to that section. Print copies will be available by the end of February.

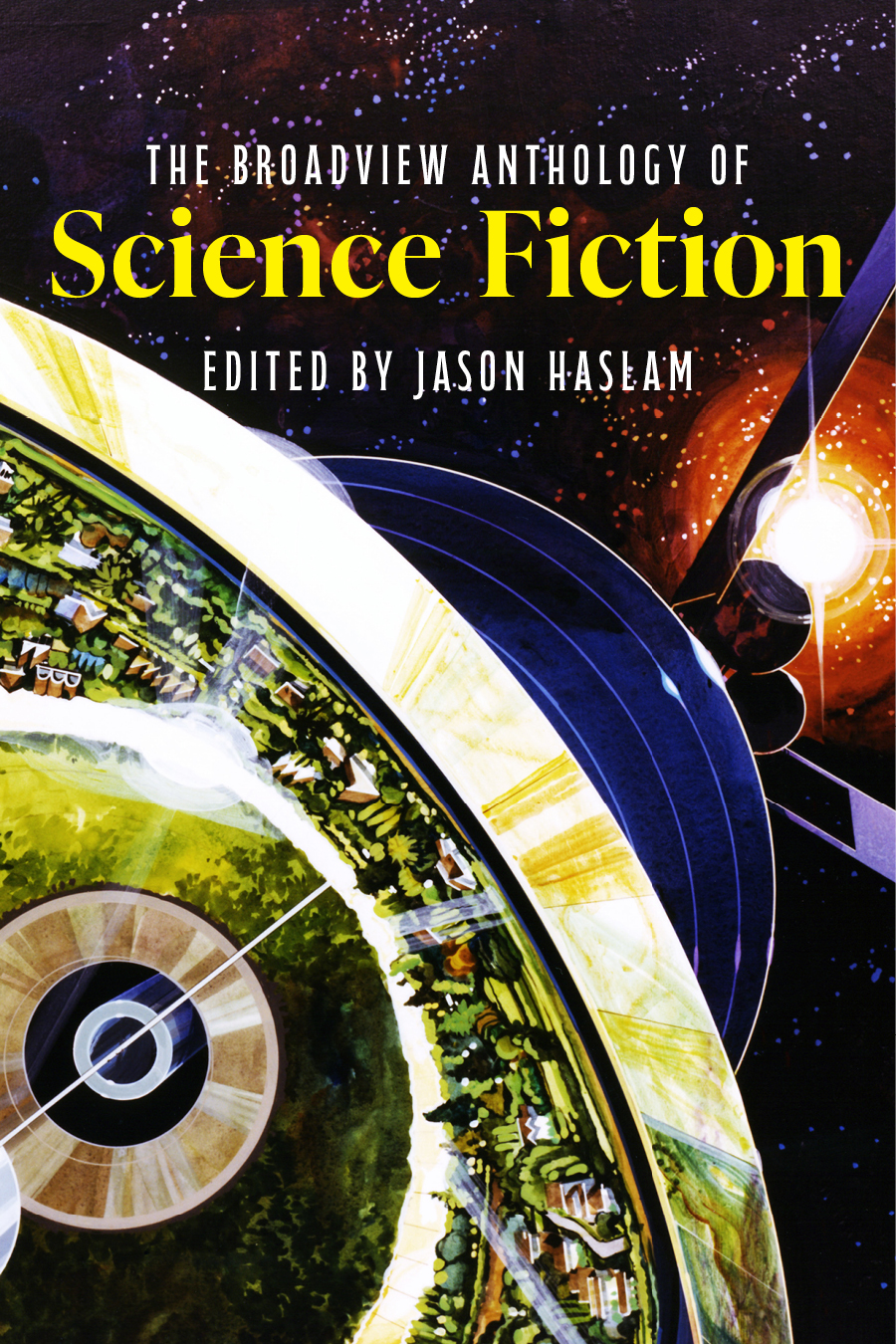

The Broadview Anthology of Science Fiction takes a “broad view” of science fiction in terms of its histories, themes, forms, and communities. Covering over two hundred years, the anthology focuses on short fiction but also includes comic strips, images, and speculative poetry. It also recognizes the wide range of futurist and SF traditions, including Afrofuturism, Indigenous Futurisms, Feminist SF, and more. Fully annotated with information about authors and texts as well as full explanatory notes, the anthology also includes an introduction that discusses the many competing definitions of—and methods of studying—science fiction and offers an historical and cultural overview of the genre.

Comments

“The Broadview Anthology of Science Fiction embraces the complexity and diversity of the SF genre, skillfully navigating the disunities that complicate and fascinate readers of SF, whilst simultaneously identifying and exploring the parallels, patterns, and shared contexts that give SF its unique shape and texture within the global media marketplace. This is an excellent starting point for students or readers who are ready to take the dive into modern literature’s most relevant and forward-thinking genre.” — Andrew Deman, University of Waterloo

“From a vast field of writing, Haslam’s selections for this science fiction anthology are a careful mix of classic and new, with proper attention paid to both canonical works and the need to expand into fresh territories and to rethink the genre anew. The contents can be twisted like a kaleidoscope to present multiple patterns and pathways, meaning readers can cover science fiction as a chronology, a set of themes, or as a vital form of cultural politics. A wonderfully enabling selection.” — Roger Luckhurst, Birkbeck, University of London

“The Broadview Anthology of Science Fiction is an impressive mix of must-read classics, forgotten treasures, and vital modern works. The table of contents is subdivided so you can easily tailor the reading to fit most classes, and the introduction gives a thorough grounding in the history of science fiction. This anthology is perfect for teaching or for those new to the genre. Haslam has done his homework and produced a collection that is essential for learning about science fiction.” — Nancee Reeves, University of Georgia