Cuneiform to Cattle Scapula: A Hands-On Approach to Writing Studies

Joyce Kinkead

One of the standout features of A Writing Studies Primer is the emphasis on hands-on activities, framed as DIY—do it yourself—activities. Students in my history of writing class uniformly cite this approach as one of their favorites, noting how these tactile exercises cement concepts in the development of writing systems around the globe.

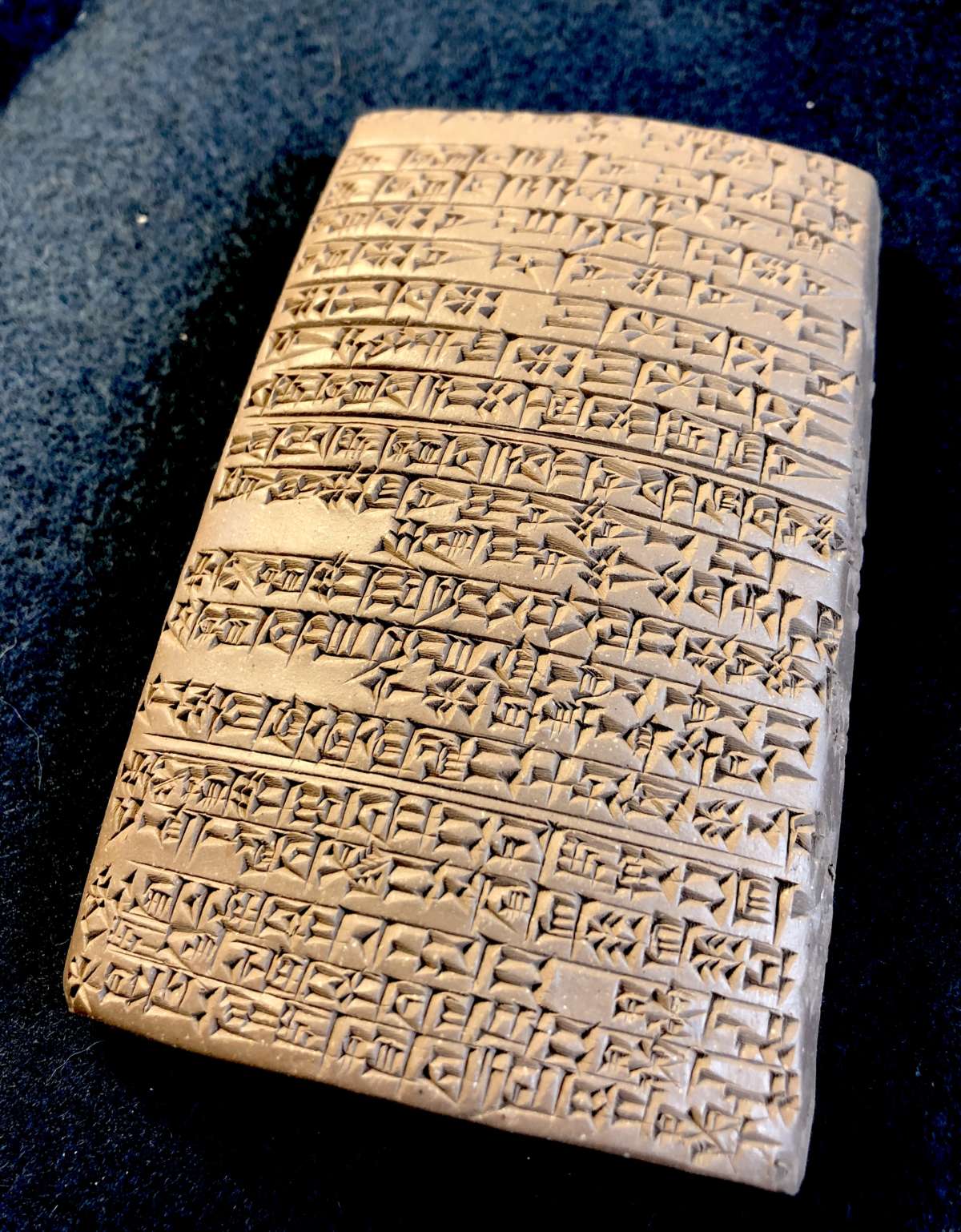

For the “Origins of Writing” chapter, we engage in three different activities. The first two take place in our Anthropology Museum on campus where docents lead them in writing their names in cuneiform and hieroglyphics. The students come to this activity no longer novices as they’ve read the chapter and listened to the first book talk of the semester, either a biography of Champollion, Cracking the Egyptian Code by Andrew Robinson (2012) or the recent The Writing of the Gods: The Race to Decode the Rosetta Stone by Edward Dolnick (2021). During this “field trip,” we are surrounded by exhibits that include actual cuneiform tablets and canopic jars.

We also have on hand a replica of a schoolboy’s lesson (original in The Louvre) that answers the age-old question “What did you do at school today?”

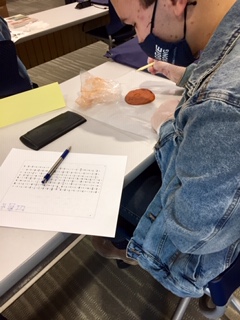

We first try out cuneiform with pencil and paper, using a guide to the wedge marks that gave the system its name. Then we receive our own clay tablets to shape into form and a “stylus” (AKA lollipop stick) to make impressions in the class. Notably, students are intrigued to figure out how to write their own names, which leads to an interesting discussion on “why are some letters—particularly vowels—missing?”

From the clay tablets, we move to papyrus and hieroglyphics. Developing about 500 years after cuneiform, which grew out of a need for more accounting as societies became more complex, hieroglyphics originated so that priests could communicate with the gods. This more spiritual approach led to beautiful writing, in contrast to the spreadsheet-style cuneiform tablets. Our contemporary scribes quickly see that developing faster systems for writing became essential, resulting in the less lovely but more efficient hieratic and demotic scripts, the latter found on the Rosetta stone. Here’s Bethany’s name in both clay and papyrus.

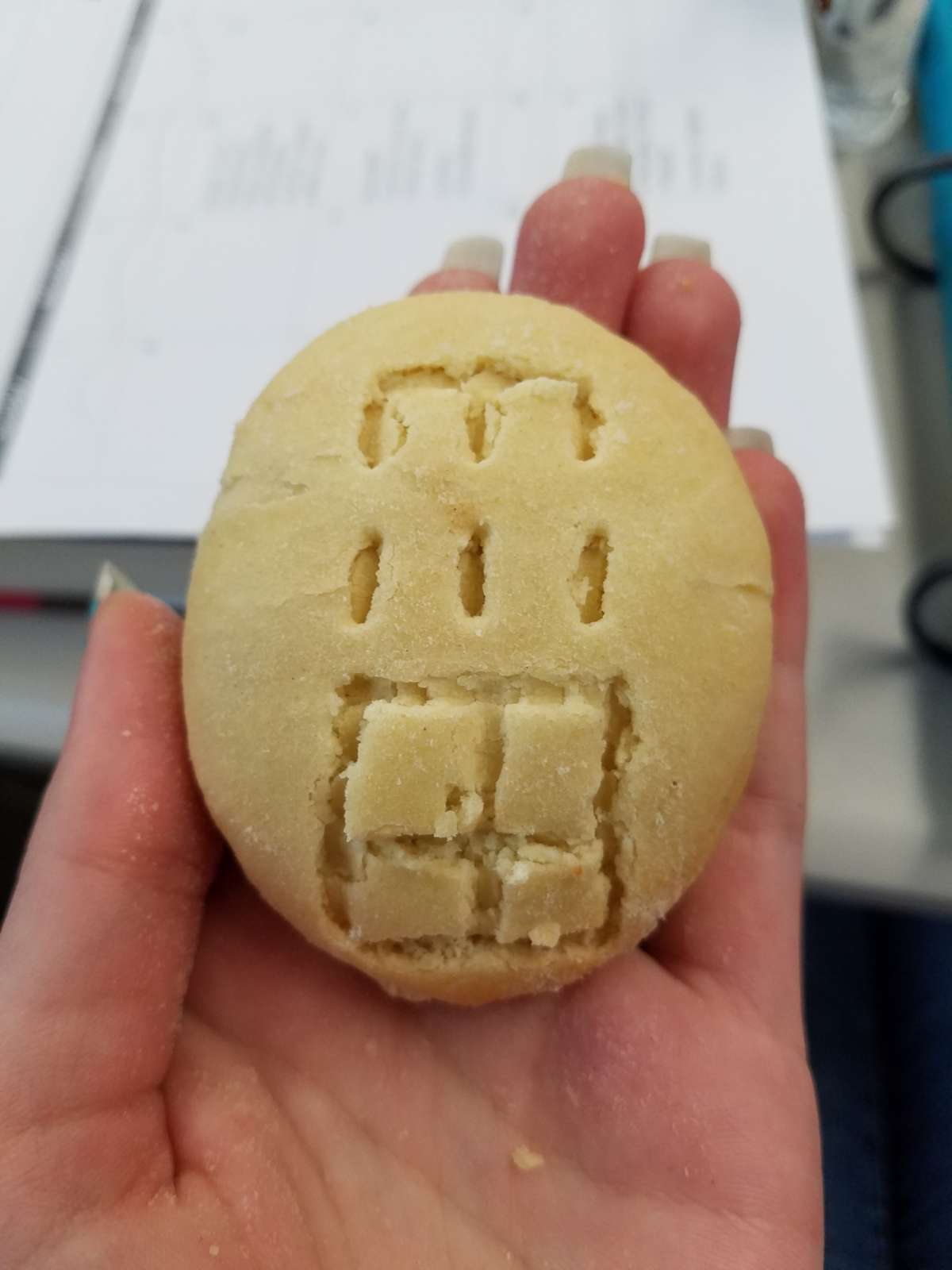

The third early writing system we visit is China’s oracle bones. Imagine being a student in a history of writing class and receiving a few weeks before the actual start of the term a message from your professor that asks “Do you have access to cattle scapula?” True confession: that’s exactly what I did when I saw that my class enrolled two students from veterinary science. To practice this writing system, we needed either scapula or tortoise shell, and the former seemed more likely. To my relief and pleasure, I received an affirmative response. Tristan and Kristi could certainly acquire that scapula. (I had not counted on their oral presentation including pictures of the cleaning process, which was certainly realistic!)

Oracle bones originated in China from a desire to know the future. Scapulimancy is enacted to predict the fate of royal families, to know about possible invading armies, or even when it’s auspicious to plant or harvest. Early Chinese characters were incised into the bone, which were then tossed into a fire with the results being interpreted by the fortune teller. Our DIY leaders used a wood-burning tool from a craft shop to demonstrate before setting their classmates to creating their own future forecasts in sugar cookies. Meant to be a treat, the cookies were actually difficult to eat as the students were reluctant to destroy their writing!

The DIY and Book Talk assignments share goals in which the students engage in actual tasks related to the development of writing and come to understand how the material culture of writing has a tremendous influence on production and consumption of text. A DIY team presents the history and then teaches classmates how to do it. Because the course is labeled “Communication Intensive” (a form of Writing Intensive common to other campuses), students are gaining skills in developing and delivering oral presentations. The teams also cite the closeness that develops with another classmate in figuring out how to cut feathers into quill pens or make paper. I supply the materials—like these wax tablets for our “write like a Roman” lesson.

Each chapter of the Primer has a DIY activity, ranging from early writing systems to asemic writing.

– Joyce Kinkead, A Writing Studies Primer