“…a shuddering horror that will thrill throughout the world.”

Stephen Donovan and Matthew Rubery’s unique new anthology Secret Commissions, published September 2012, collects nineteen works of investigative journalism from the Victorian age. The articles capture the frequently stark and sinister social conditions of nineteenth-century Britain, and bring to life the sense of horror and frustration surrounding such controversial issues as poverty, prostitution, and infanticide.

Stephen Donovan and Matthew Rubery’s unique new anthology Secret Commissions, published September 2012, collects nineteen works of investigative journalism from the Victorian age. The articles capture the frequently stark and sinister social conditions of nineteenth-century Britain, and bring to life the sense of horror and frustration surrounding such controversial issues as poverty, prostitution, and infanticide.

This excerpt comes from George R. Sims’ “How the Poor Live,” an exposé on living conditions in metropolitan London; it was serialized in thirteen weekly instalments from June 2 to August 25, 1883 and was widely reprinted in the years that followed alongside appeals for charitable funds and official commissions on housing and poverty.

We have reached the attic, and in that attic we see a picture which will be engraven on our memory for many a month to come.

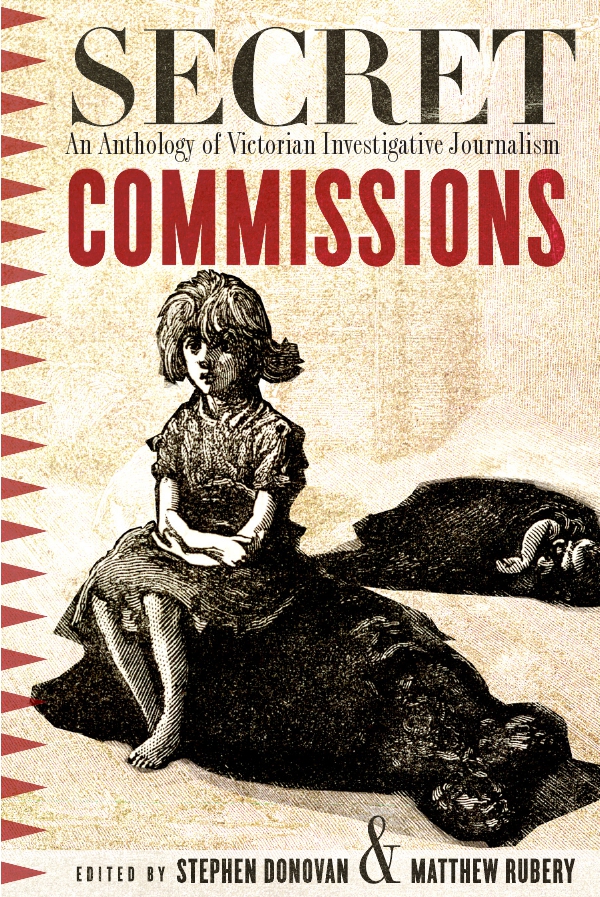

The attic is almost bare; in a broken fireplace are some smouldering embers, a log of wood lies in front like a fender. There is a broken chair trying to steady itself against a wall black with the dirt of ages. In one corner, on a shelf, is a battered saucepan and a piece of dry bread. On the scrap of mantel still remaining embedded in the wall, is a rag; on a bit of cord hung across the room are more rags—garments of some sort, possibly; a broken flower-pot props open a crazy window-frame, possibly to let the smoke out, or in—looking at the chimney-pots below, it is difficult to say which; and at one side of the room is a sack of Heaven knows what—it is a dirty, filthy sack, greasy and black and evil looking. I cannot guess what was in it if I tried, but what was on it was a little child—a neglected, ragged, grimed, and bare-legged little baby girl of four. There she sat, in the bare squalid room, perched on the sack, erect, motionless, expressionless, on duty.

She was “a little sentinel,” left to guard a baby that lay asleep on the bare boards behind her, its head on its arm, the ragged remains of what had been a shawl flung over its legs.

That baby needed a sentinel to guard it, indeed. Had it crawled a foot or two it would have fallen head-foremost in that unprotected, yawning abyss of blackness below. In case of some such proceeding on its part, the child of four had been left “on guard.”

The furniture of the attic, whatever it was like, had been seized the week before for rent. The little sentinel’s papa—this we unearthed of the “deputy” of the house later on—was a militiaman and away; the little sentinel’s mamma has gone out on “a arrand,” which, if it was anything like her usual “arrands,” the deputy below informed us, would bring her home about dark, very much the worse for it. Think of that little child, keeping guard on that dirty sack for six or eight hours at a stretch—think of her utter loneliness in that bare, desolate room, every childish impulse checked, left with orders “not to move or I’ll kill yer,” and sitting there often till night and darkness came on, hungry, thirsty, and tired herself, but faithful to her trust to the last minute of the drunken mother’s absence. “Bless yer! I’ve known that young ’un sit there eight ’our at a stretch. I’ve seen her there of a mornin’ when I’ve come up to see if I could git the rint, and I’ve seen her there when I’ve come agin’ at night”—says the deputy. “Lor, that ain’t nothing—that ain’t.”

Nothing! It is one of the saddest pictures I have seen for many a day. Poor little baby-sentinel—left with a human life in its sole charge at four—neglected and overlooked: what will its girl life be, when it grows old enough to think? I should like some of the little ones whose every wish is gratified, who have but to whimper to have, and who live surrounded by loving, smiling faces, and tendered by gentle hands, to see the little child in the bare garret sitting sentinel over the sleeping baby on the floor, and budging never an inch throughout the weary day from the place that her mother had bidden her stay in.

With our minds full of this pathetic picture of child-life in the “Homes of the Poor,” we descend the crazy staircase, and get out into as much light as can find its way down these narrow alleys.

From: George R. Sims and Frederick Barnard, “How the Poor Live,” Pictorial World 40ns/483os (2 June 1883), 609–10.