Instructional Treatise from A Book for Governesses

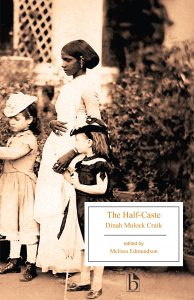

The Half-Caste

The following is an excerpt from Appendix C of our recently published The Half-Caste by Dinah Mulock Craik, edited by Melissa Edmundson.

[volume editor’s note] The social and financial status of the Victorian governess was a topic of debate throughout the nineteenth century…Emily Peart’s A Book for Governesses (1868) provides an example of the many instructional treatises designed to prepare young women for life as governesses, especially women who unexpectedly found themselves seeking employment due to financial obligations or other family misfortune.

From Emily Peart’s A Book for Governesses (Edinburgh: W. Oliphant, [1868])

It is not specially for those who have been brought up and educated with a view to their being governesses, and who, consequently, have accepted the occupation as their natural work, that these pages have been written; they are rather intended for those who, by sudden strokes of adverse fortune, or by change in one shape or another, are brought down from ease and wealth to a state of dependence upon work for their daily bread.

Work is a noble and a glorious thing—a blessing and a boon. In one way or another, it is the happy lot of all; for rank and riches exempt no one from work of some kind. But sometimes the sudden shock, which reveals so unexpected a fact as poverty, has scarcely passed, before the truth presses on the heart and brain of the sufferer, “Henceforth, for the hitherto unnoticed needs of daily life, I have none but myself to look to.” Imagine for a moment, cherished daughter of a happy home, what the feeling is that you have no right to utter the sweet words, “My home;”—imagine what it is to be away from friends, companions, the associates of your youth, to have to bear the coldness of strangers, the exactions of employers, the patronage of inferiors; to be measured exactly for how much you are worth in a business-like and financial point of view; your capabilities questioned, your acquirements displayed, your appearance criticised; your manners, your deportment, your dress commented upon; and all to be added up and decided, and their sum total to be told out in £, s. d. Think of the same routine of work day by day—work, not to be rewarded by a mother’s kiss, a father’s smile, and the joy of the evening gathering round the family hearth, —and you will have pictured to yourself the lot of hundreds of your sisters; on many of whom it has fallen as a sudden blight. Let such remember that it is not by smothering sorrow, or by trying to keep it down, as if it did not exist, that it is to be conquered; but by bravely facing it and dealing with it. It is there in its intensity; let them realize it, and then set about the best way of bearing it. […]

There is an excess of sensitiveness in the feelings of a girl who has lost the shelter of a home, when she knows for the first time her position, which must be felt to be in the least understood. She is suffering, and suffering makes her weak. It is not to the always poor, but to the suddenly-made poor, that the slight, meant or unmeant, comes with keen meaning. In sound health you never feel a hundred influences, which in weakness and sickness affect you most painfully. Actions, which before would have passed unnoticed, are misconstrued; favours, which before would have been joyfully accepted, are now refused with a morbid shrinking; words, which before would have been unheeded, are full of new and stinging meaning; eyes washed with hot tears are quick to see things which do not really exist. The shock sustained, and the bewilderment accompanying it, absorb, and cannot but absorb, for a time, every thought and feeling; and the breaking heart finds utterance in the helpless question: “What can I do?” Well, then, in the first place, you can be silent; then you can be patient; and then you can be brave. […]

Be willing to be questioned,—not impertinently questioned, as to family affairs and plans; but as to everything pertaining to your new duties shrink from no questioning, painful as it may and will be. Your accomplishments are not now to be the theme of loving friends and admiring acquaintances, but the means of an honourable independence and of obtaining money. Face the real truth; they are simply to be calculated at trade value; and “the value of a thing is just as much as it will bring.” Do not too confidently say you are sure you can do so and so—you are perfectly equal to that— you are not in the least afraid, and so forth. If you are not afraid, you ought to be with a right fear. Say simply what your education has been, what you believe you most excel in, and your determination to do your best. Far rather risk losing a good situation by stating truthfully only what you can do, than for a moment profess to do what you cannot. […]

Try not to decide as to the merits of your situation until you have been in it for six months. You will give a very different verdict at the end of this time from that which you would have given at the beginning. Do not fill your letters to your friends with accounts which at the end of a year you may wish had never been written. Again and again consider you have all to learn; and the first lesson to you, as to all others, is the most difficult.